Architecture overview

Terminology

Backstage is organized into three main components, each catering to different groups of contributors who interact with Backstage in distinct ways.

- Core - This includes the base functionality developed by core developers within the open-source project.

- App - The app represents a deployed instance of a Backstage application, customized and maintained by app developers, typically a productivity team within an organization. It integrates core functionalities with additional plugins.

- Plugins - These provide additional functionalities to enhance the usefulness of your Backstage app. Plugins can be company-specific or open-sourced and reusable.

Overview

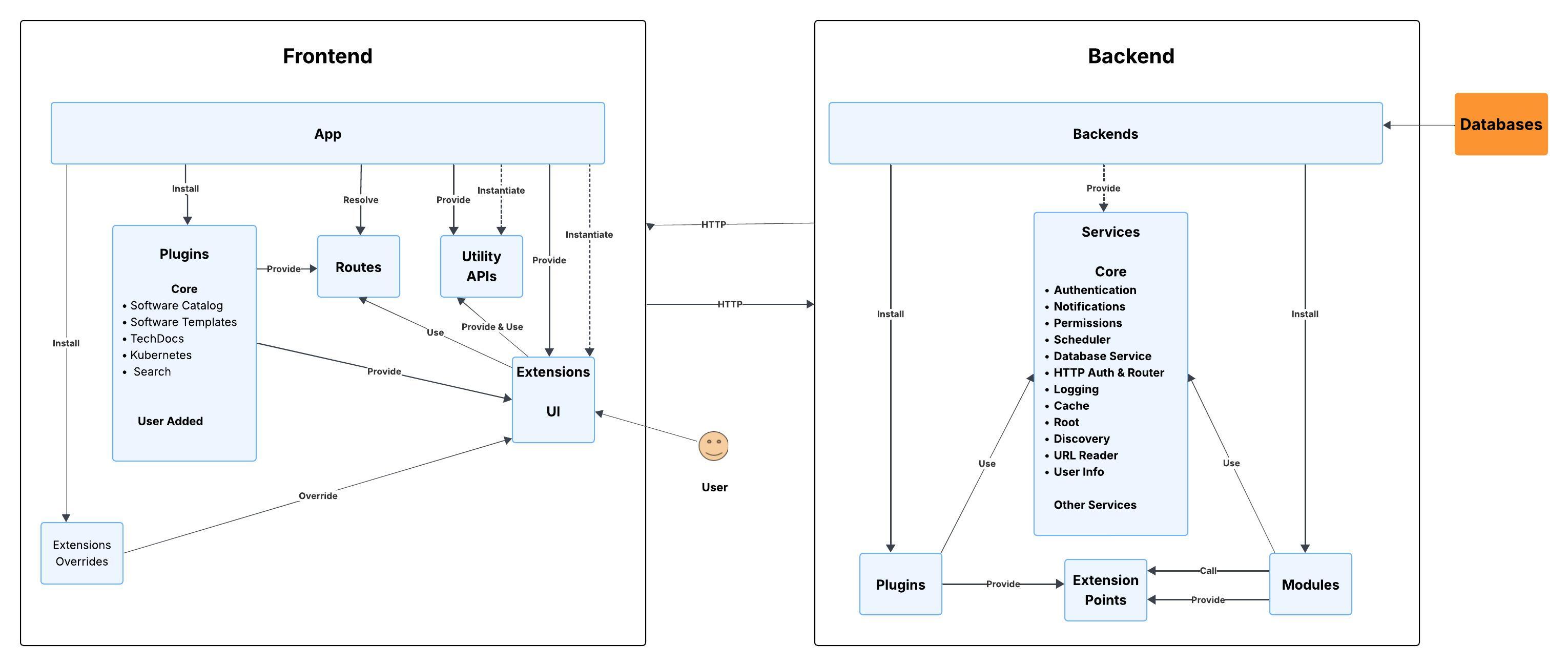

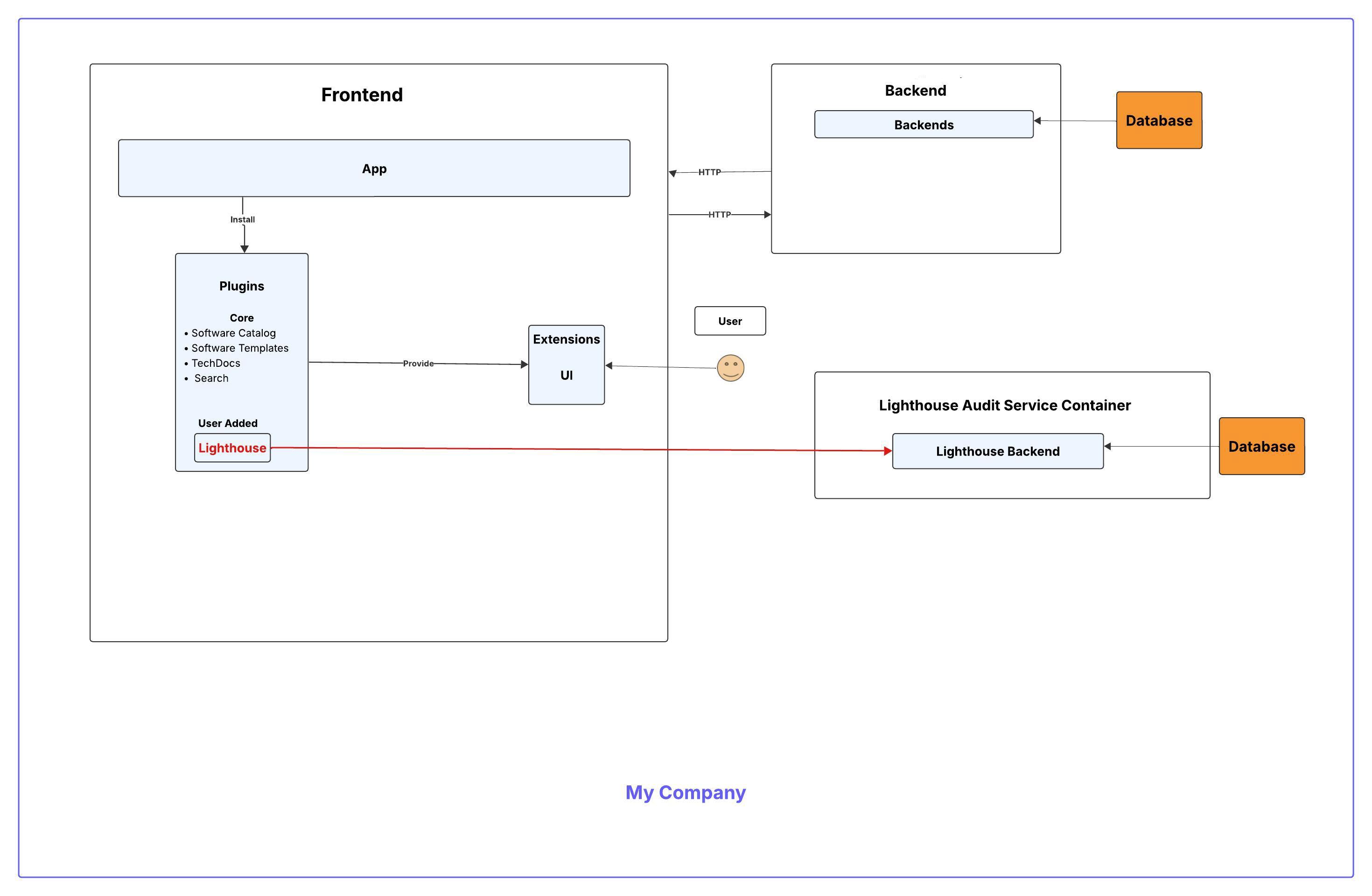

The following diagram shows a high level view of the overall architecture of Backstage. Running this architecture in a real environment typically involves containerizing the components. Various commands are provided for accomplishing this.

There are 3 main components in this architecture:

- The frontend includes the core Backstage UI which is an extension that interacts directly with the user to present the information from the integrated core feature plugins, and other plugins added by a user.

- The backend includes the backend plugins, core services, and other services. This is the server-side part of Backstage that is responsible for wiring things together. You can deploy more than one backend, and more than one backend container, depending on your need to scale and isolate individual features.

- Databases host your Backstage data.

Frontend building blocks

The architectural diagram provides an overview of the different building blocks and the other blocks that each of them interacts with.

App

This is the app instance itself that you create and use as the root of your Backstage frontend application. It does not have any direct functionality in and of itself, but is simply responsible for wiring things together.

Extensions

Extensions are the building blocks that build out both the visual and non-visual structure of the application. There are both built-in extensions provided by the app itself as well as extensions provided by plugins. Each extension is attached to a parent with which it shares data and can have any number of children of its own. It is up to the app to wire together all extensions into a single tree known as the app extension tree. It is from this structure that the entire app can then be instantiated and rendered.

User Interface

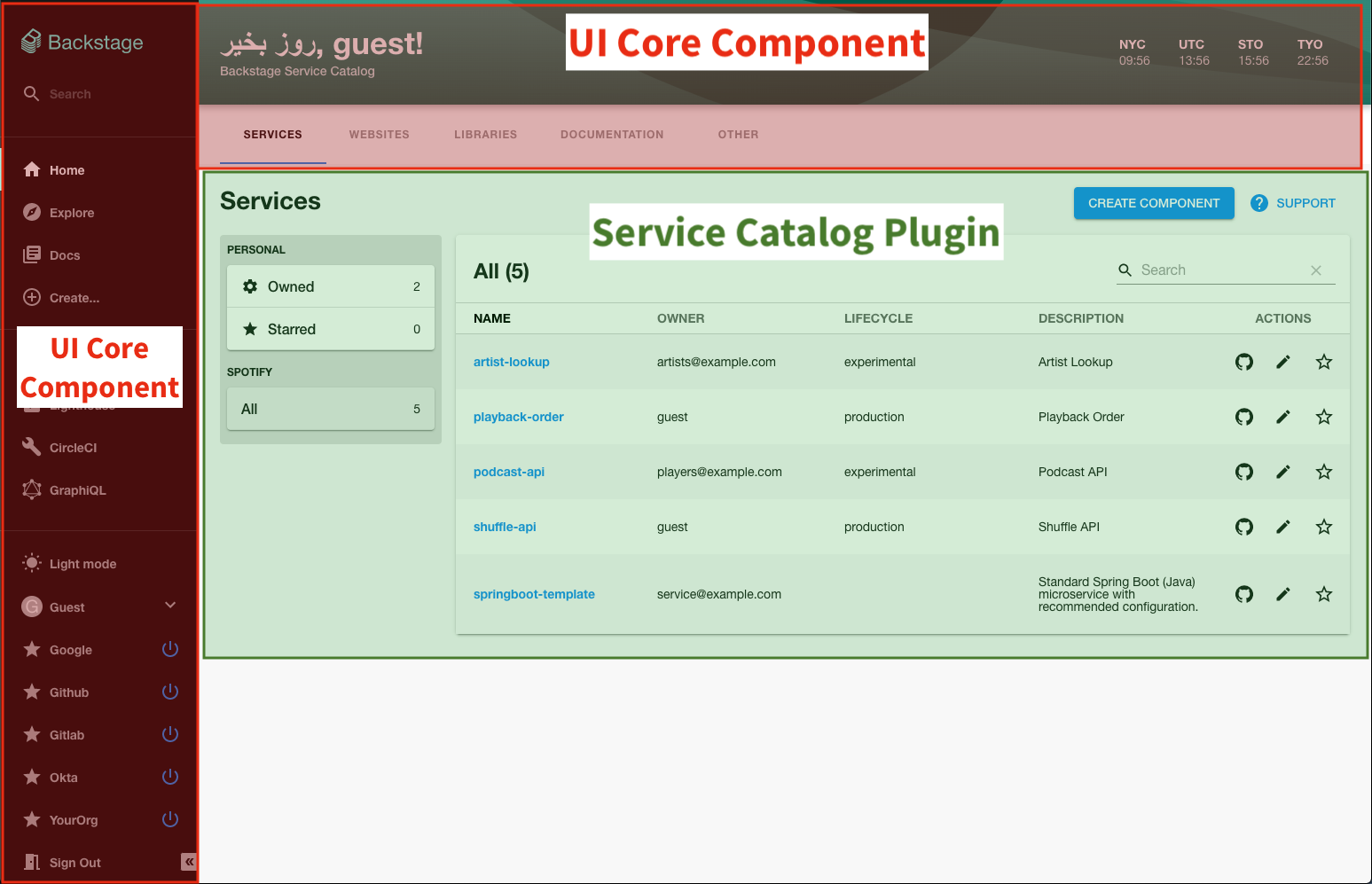

The UI is one of the extensions in the frontend. It is a thin, client-side wrapper around a set of plugins. It provides some core UI components and libraries for shared activities such as config management. [live demo]

Each plugin typically makes itself available in the UI on a dedicated URL. For example, the Service Catalog plugin is registered with the UI on /catalog.

Frontend plugins

Plugins provide the actual features inside an app. The size of a plugin can range from a tiny component to an entire new system in which other plugins can be composed and integrated. Plugins can be completely standalone or built on top of each other to extend existing plugins and augment their features. Plugins can communicate with each other by composing their extensions or by sharing Utility APIs and routes.

Backstage includes the following set of core plugins:

- Software Catalog - A centralized system that contains metadata for all your software, such as services, websites, libraries, ML models, data pipelines, and so on. It can also contain metadata for the physical or virtual infrastructure needed to operate a piece of software. The software catalog can be viewed and searched through a UI.

- Software Templates - A tool to help you create components inside Backstage. A template can load skeletons of code, include some variables, and then publish the template to a location, such as GitHub.

- TechDocs - A docs-like-code solution built into Backstage. Documentation is written in Markdown files which lives together with the code.

- Kubernetes - A tool that allows developers to check the health of their services whether it is on a local host or in production.

- Search - Search for information in the Backstage ecosystem. You can customize the look and feel of each search result and use your own search engine.

Plugin architecture provides greater detail about the architecture of the plugins themselves.

Extension Overrides

In addition to the built-in extensions and extensions provided by plugins, it is also possible to install extension overrides. This is a collection of extensions with high priority that can replace existing extensions. They can for example be used to override an individual extension provided by a plugin, or install a completely new extension, such as a new app theme.

Utility APIs

Utility APIs provide functionality that makes it easier to build plugins, make it possible for plugins to share functionality with other plugins, as well as serve as a customization point for integrators to change the behaviour of the app. Each Utility API is defined by a TypeScript interface as well as a reference used to access the implementations. The implementations of Utility APIs are defined by extensions that are provided and can be overridden the same as any other extension.

Routes

The Backstage routing system adds a layer of indirection that makes it possible for plugins to route to each other's extensions without explicit knowledge of what URL paths the extensions are rendered at or if they even exist at all. It makes it possible for plugins to share routes with each other and dynamically generate concrete links at runtime. It is the responsibility of the app to resolve these links to actual URLs, but it is also possible for integrators to define their own route bindings that decide how the links should be resolved. The routing system also lets plugins define internal routes, aiding in the linking to different content in the same plugin.

Backend building blocks

The architectural diagram provides an overview of the different building blocks, and the other blocks that each of them interact with.

Backend

This is the backend instance itself, which you can think of as the unit of deployment. It does not have any functionality in and of itself, but is simply responsible for wiring things together.

It is up to you to decide how many different backends you want to deploy. You can have all features in a single one, or split things out into multiple smaller deployments, depending on your need to scale and isolate individual features.

Backend plugins

Plugins provide the actual features. They operate completely independently of each other. If plugins want to communicate with each other, they must do so over the wire. There can be no direct communication between plugins through code. Because of this constraint, each plugin can be considered to be its own microservice.

Plugin architecture provides greater detail about the architecture of the plugins themselves.

Services

Services provide utilities to help make it simpler to implement plugins, so that each plugin doesn't need to implement everything from scratch. There are many built-in core services, such as the ones for logging, database access, and reading configuration, but you can also import third-party services, or create your own.

Services are also a customization point for individual backend installations. You can override services with your own implementations, as well as make smaller customizations to existing services.

Extension Points

Many plugins have ways in which you can extend them, for example entity providers for the Catalog, or custom actions for the Scaffolder. These extension patterns are now encoded into Extension Points.

Extension Points look a little bit like services, since you depend on them just like you would a service. A key difference is that extension points are registered and provided by plugins or modules themselves, based on what customizations each of them want to expose.

Extension Points are exported separately from the plugin or module instance itself, and it is possible to expose multiple different extension points at once. This makes it easier to evolve and deprecate individual Extension Points over time, rather than dealing with a single large API surface.

Modules

Modules use Extension Points to add new features to other plugins or modules. They might for example add an individual Catalog Entity Provider, or one or more Scaffolder Actions.

Each module may only use Extension Points that belong to a single plugin, and the module must be deployed together with that plugin in the same backend instance. Modules may only communicate with their plugin or other modules through the registered extension points.

Just like plugins, modules also have access to services and can depend on their own service implementations. They will however share services with the plugin that they extend - there are no module-specific service implementations.

Databases

The databases host your Backstage data. The Backstage backend and its built-in plugins are based on the Knex library, and set up a separate logical database per plugin. This gives great isolation and lets them perform migrations and evolve separately from each other.

The Knex library supports a multitude of databases, but Backstage at this time of writing is tested primarily against two of them:

- SQLite, which is mainly used as an in-memory mock/test database

- PostgreSQL, which is the preferred production database.

Other databases such as the MySQL variants are reported to work but aren't fully tested yet.

You can find instructions on setting up a PostgreSQL for your Backstage instance in Database. Configuring Plugin Databases provides information on how to configure a database for a plugin.

Plugin architecture

Architecturally, plugins can take three forms:

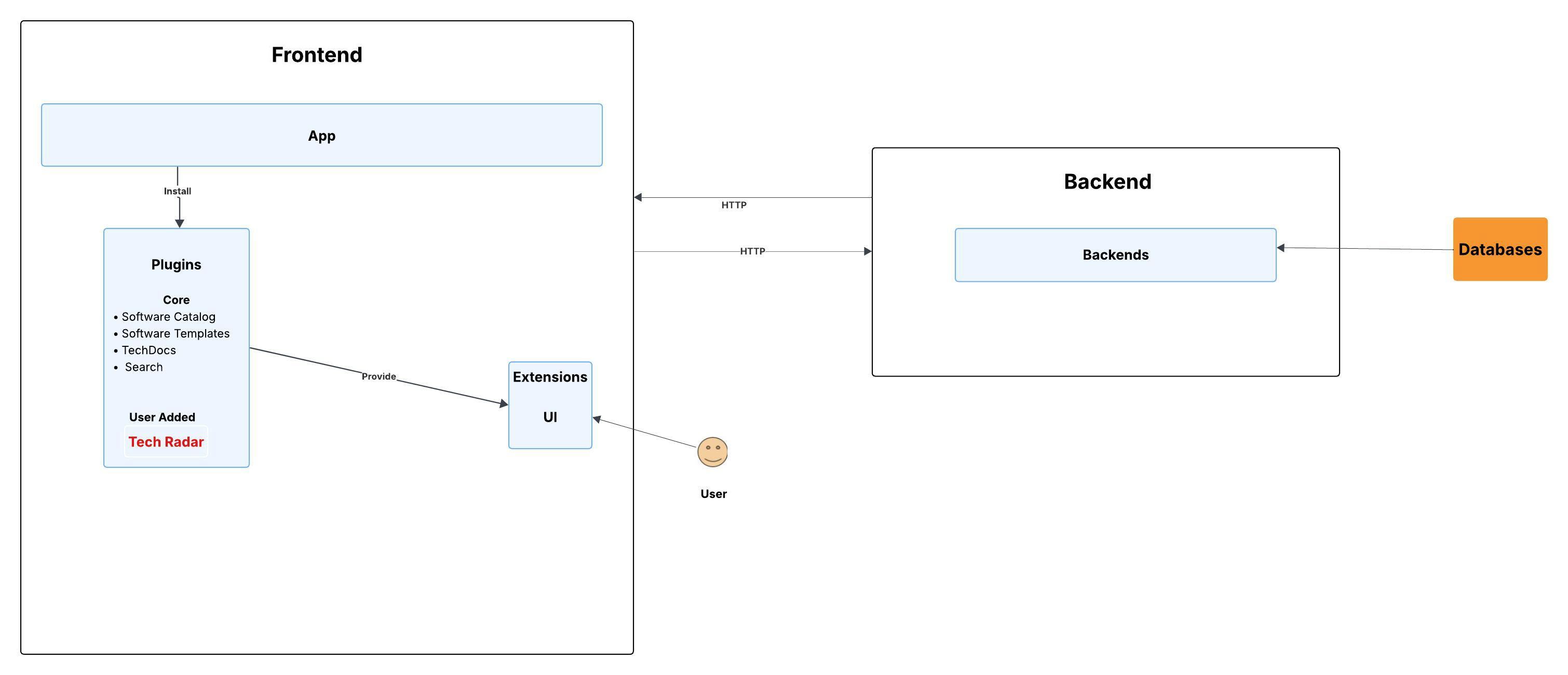

Standalone plugins

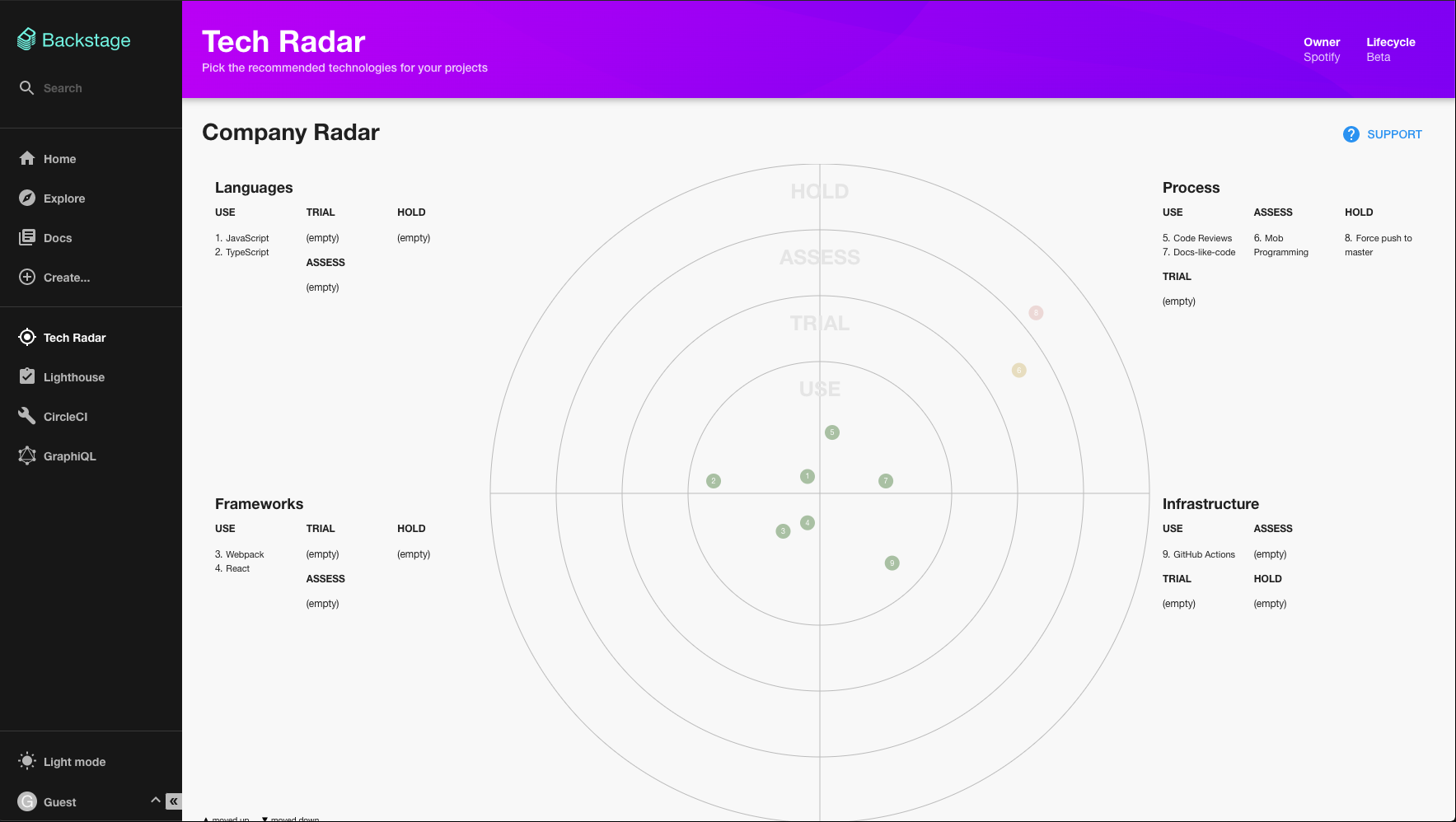

Standalone plugins run entirely in the browser. The Tech Radar plugin, for example, simply renders hard-coded information. It doesn't make any API requests to other services.

The architecture of the Tech Radar installed into a Backstage app is very simple. You just need to add Tech Radar as a frontend plugin into your app, as shown in the following diagram.

NOTE:

The following diagram does not show the detailed contents of the frontend and backend containers in order to highlight the changes that pertain to the addition of the specified plugin.

Once the plugin has been added, then you can view the Tech Radar information in the Backstage UI.

Service backend plugins

Service backend plugins make API requests to a service which is within the purview of the organization running Backstage.

The Lighthouse plugin, for example, makes requests to the lighthouse-audit-service. The lighthouse-audit-service is a microservice which runs a copy of Google's Lighthouse library and stores the results in a PostgreSQL database.

The Lighthouse plugin is added to the frontend. The lighthouse-audit-service container is already publicly available in Docker Hub and can be downloaded and run with

docker run spotify/lighthouse-audit-service:latest

NOTE:

The following diagram does not show the detailed contents of the frontend and backend, in order to highlight the changes that pertain to the addition of the specified plugin.

The software catalog in Backstage is another example of a service backend plugin. It retrieves a list of services, or "entities", from the Backstage Backend service and renders them in a table for the user.

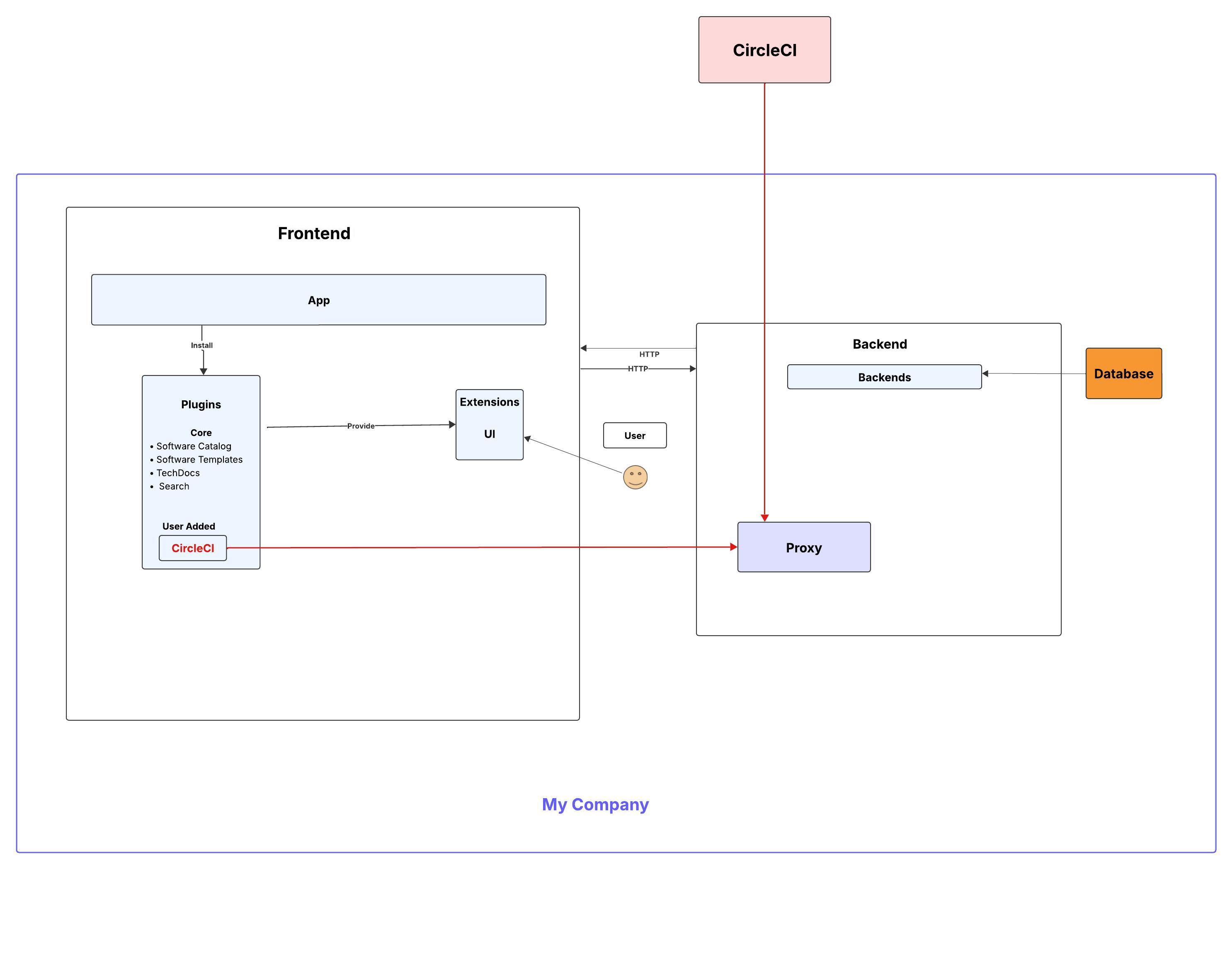

Third-party backend plugins

Third-party backend plugins are similar to service backend plugins. The main difference is that the service which backs the plugin is hosted outside of the ecosystem of the company hosting Backstage.

The CircleCI plugin is an example of a third-party backend plugin. CircleCI is a SaaS service which can be used without any knowledge of Backstage. It has an API which a Backstage plugin consumes to display content.

Requests going to CircleCI from the user's browser are passed through a proxy service that Backstage provides. Without this, the requests would be blocked by Cross Origin Resource Sharing policies which prevent a browser page served at https://example.com from serving resources hosted at https://circleci.com.

NOTE: The following diagram does not show the detailed contents of the frontend and backend, in order to highlight the changes that pertain to the addition of the specified plugin.

Package Architecture

Backstage relies heavily on NPM packages, both for distribution of libraries, and structuring of code within projects. While the way you structure your Backstage project is up to you, there is a set of established patterns that we encourage you to follow. These patterns can help set up a sound project structure as well as provide familiarity between different Backstage projects.

The following diagram shows an overview of the package architecture of Backstage. It takes the point of view of an individual plugin and all of the packages that it may contain, indicated by the thicker border and italic text. Surrounding the plugin are different package groups which are the different possible interface points of the plugin. Note that not all library package lists are complete as packages have been omitted for brevity.

Overview

The arrows in the diagram above indicate a runtime dependency on the code of the target package. This strict dependency graph only applies to runtime

dependencies, and there may be devDependencies that break the rules of this table for the purpose of testing. While there are some arrows that show a dependency on a collection of frontend, backend and isomorphic packages, those still have to abide by important compatibility rules shown in the bottom left.

The app and backend packages are the entry points of a Backstage project. The app package is the frontend application that brings together a collection of frontend plugins and customizes them to fit an organization, while the backend package is the backend service that powers the Backstage application. Worth noting is that there can be more than one instance of each of these packages within a project. Particularly the backend packages can benefit from being split up into smaller deployment units that each serve their own purpose with a smaller collection of plugins.

Plugin Packages

A typical plugin consists of up to five packages, two frontend ones, two backend, and one isomorphic package. All packages within the plugin must share a common prefix, typically of the form @<scope>/plugin-<plugin-id>, but alternatives like backstage-plugin-<plugin-id> or @<scope>/backstage-plugin-<plugin-id> are also valid. Along with this prefix, each of the packages have their own unique suffix that denotes their role. In addition to these five plugin packages it's also possible for a plugin to have

additional frontend and backend modules that can be installed to enable optional features. For a full list of suffixes and their roles, see the Plugin Package Structure ADR.

The -react, -common, and -node plugin packages together form the external library of a plugin. The plugin library enables other plugins to build on top of and extend a plugin, and likewise allows the plugin to depend on and extend other plugins. Because of this, it is preferable that plugin library packages allow duplicate installations of themselves, as you may end up with a mix of versions being installed as dependencies of various plugins. It is also forbidden for plugins to directly import non-library packages from other plugins, all communication between plugins must be handled through libraries and the application itself.

Frontend Packages

The frontend packages are grouped into two main groups. The first one is "Frontend App Core", which is the set of packages that are only used by the app package itself. These packages help build up the core structure of the app as well as provide a foundation for the plugin libraries to rely upon.

The second group is the rest of the shared packages, further divided into "Frontend Plugin Core" and "Frontend Libraries". The core packages are considered particularly stable and form the core of the frontend framework. Their most important role is to form the boundary around each plugin and provide a set of tools that helps you combine a collection of plugins into a running application. The rest of the frontend packages are more traditional libraries that serve as building blocks to create plugins.

Backend Packages

The backend library packages do not currently share a similar plugin architecture as the frontend packages. They are instead simply a collection of building blocks and patterns that help you build backend services. This is however likely to change in the future.

Common Packages

The common packages are the packages effectively depended on by all other pages. This is a much smaller set of packages but they are also very pervasive. Because the common packages are isomorphic and must execute both in the frontend and backend, they are never allowed to depend on any of the frontend or backend packages.

The Backstage CLI is in a category of its own and is depended on by virtually all other packages. It's not a library in itself though, and must always be a development dependency only.

Deciding where you place your code

It can sometimes be difficult to decide where to place your plugin code. For example, should it go directly in the -backend plugin package or in the -node package? As a general guideline you should try to keep the exposure of your code as low as possible. If it doesn't need to be public API, it's best to avoid. If you don't need it to be used by other plugins, then keep it directly in the plugin packages.

Below is a chart to help you decide where to place your code.

Cache

The Backstage backend and its built-in plugins are also able to leverage cache stores as a means of improving performance or reliability. Similar to how databases are supported, plugins receive logically separated cache connections, which are powered by Keyv under the hood.

At this time of writing, Backstage can be configured to use one of five cache stores:

memorymemcacheredisvalkeyinfinispan

memory is primarily used for local development, for production deployments, we recommend using one of the other cache stores. The right cache store for your Backstage instance will depend on your own run-time constraints and those required of the plugins you're running.

Use memory for cache

backend:

cache:

store: memory

Use memcache for cache

backend:

cache:

store: memcache

connection: user:pass@cache.example.com:11211

Use Redis for cache

backend:

cache:

store: redis

connection: redis://user:pass@cache.example.com:6379

Use Infinispan for cache

Minimal configuration

- defaults, no

authentication, expects cache namedcacheand host127.0.0.1:11222)

backend:

cache:

store: infinispan

Extended configuration

- Unlike Redis, Infinispan will not create the cache for you. It's expected you've configured the cache in your infinispan server prior to configuration here.

- A full list of configuration items are available: https://docs.jboss.org/infinispan/hotrod-clients/javascript/1.0/apidocs/module-infinispan.html including support for backup clusters.

backend:

cache:

store: infinispan

infinispan:

servers:

- host: 127.0.0.1

port: 11222

cacheName: backstage-cache

mediaType: application/json

authentication:

enabled: true

userName: yourusername

password: yourpassword

saslMechanism: PLAIN

Contributions supporting other cache stores are welcome!